The Making of Hecate

If Kylie Bracknell, co-translator and director of Hecate, was asked that classic question – what three figures from history would you invite to a dinner party? – one of her guests would be William Shakespeare.

“I would ask him why he included the three witches in Macbeth. And why Hecate is only in the play for such a short time. Then I’d ask him to stay on after dinner to see Hecate and tell me what he thought.” Bracknell says. She’d like to think he’d enjoy it!

Shakespeare’s work has been translated countless times into numerous languages. It’s one of the reasons it has stood the test of time – that and the fact that its themes remain relevant across cultures and throughout the ages. So perhaps it was inevitable in a time when there is renewed focus on reviving Indigenous languages that Shakespeare would be translated into an Australian Indigenous language. But that doesn’t mean it was an easy task for the many people behind Yirra Yaakin’s production.

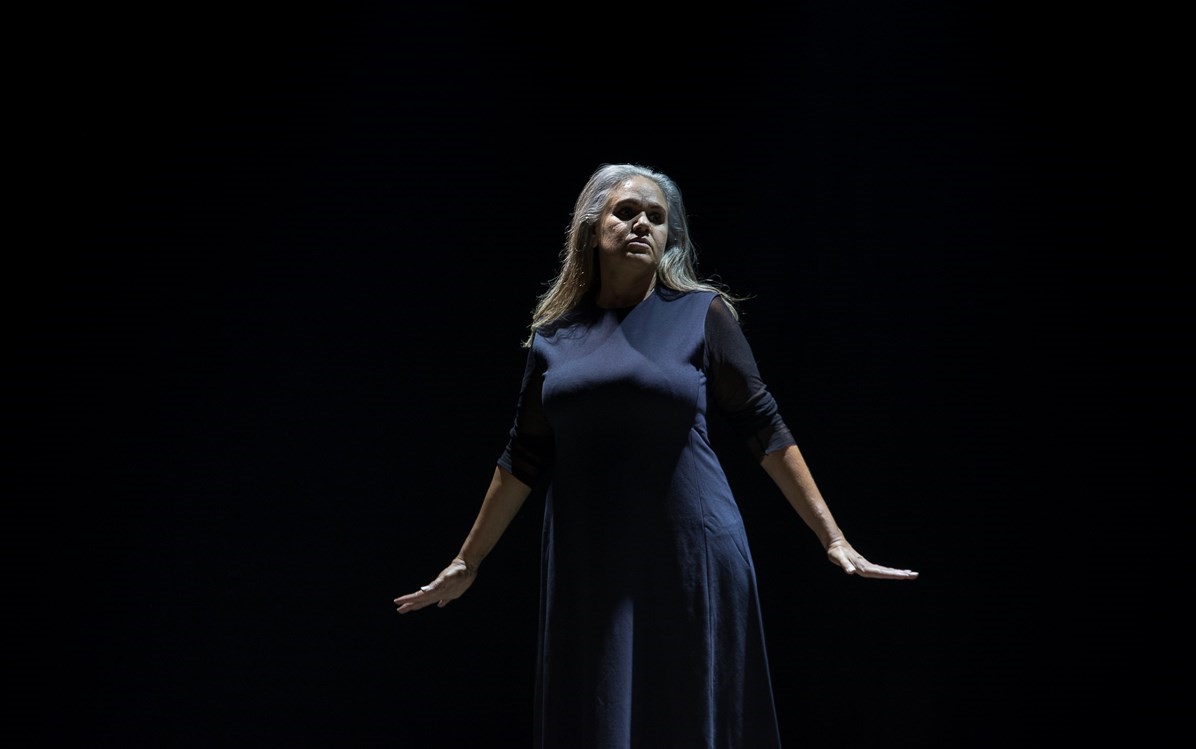

Image: Dana Weeks

When Kyle J Morrison first floated the idea of putting his favourite Shakespeare play onstage in Noongar language, Bracknell thought he was crazy! It was just nine months before London’s Globe to Globe Festival and there just wasn’t time. Instead she translated selected sonnets which were performed to great success. But the idea didn’t go away, and she came on board to help out.

As she explains it: ‘I wasn’t particularly drawn to Shakespeare or this play but I appreciated that we need more high-quality productions to document and showcase our language, so it felt important to get involved.”

And so began the “mammoth task” of translating Shakespeare’s text into Noongar.

“This is not a cultural project per se.” Bracknell is quick to point out. “It is a staging of a Shakespeare work, an adaption just like you might do in English. But in this instance it’s through Noongar language expression.”

Image: Dana Weeks

Bell Shakespeare become involved and it was during an early creative development session that Bracknell had her “light bulb moment”.

“It’s Hecate. She’s the pivotal character.” She recalls realising. “Lots of stagings of Macbeth cut her scene out, but what if we told the story from her perspective. What if she were the focus?”

This way of approaching a Noongar version of the play makes perfect sense when considering the matriarchal nature of Noongar culture. The decision to stage a version of Macbeth with such a focus on the female perspective was not really a decision – it is just a part of who Bracknell is and what her culture is about.

“We acknowledge the female strength in everything. In metaphor and in fact the Mother Earth is our life source – in the womb we survive purely from our mother. Everyone is born of a woman. Then when we die we return to the earth – to Mother Earth. Women give life, care for life and grieve in death. This was the essence of the story I wanted to tell.”

There were obviously practical problems to overcome in translating Shakespeare’s English into a language that only has about 1,500 words.

“Noongar is a pure language – there is not a lot of vocab to draw from”, Bracknell explains. “We don’t have a lot of synonyms in the actual words – different meaning comes from the expression used. It’s the way a word is said that changes the meaning.”

This led to another development in the creative process – Bracknell becoming the show’s director. It’s a decision that was an obvious progression from her role as translator. She knew that her adaptation couldn’t be confined to the page.

“You have to remember that only 1% of Noongar people speak their language. So for the actors the process has been about reclaiming a language they didn’t fully know. They have had to learn not only the words their characters say, but also how to portray them – what speed or inflection to use to show the differentiation in the meaning of the words.

“It was necessary to be mindful of the rhythm and beauty of Noongar language – in both the translation and the performance. So many translations are word for word and that can create a stilted language – that’s just not how Noongar works. The translation had to be mindful of the poetry and expression of the language itself, but then the actors also had to take this with them.”

Image: Dana Weeks

This also meant the actors taking the language on in a physical sense. During the rehearsal period Bell Shakespeare’s James Evans was struck by the way the actors performed the text.

“The physicality of the actors and the language go hand in hand. And the way that they express themselves with gesture and body and movement is also a part of the language, and that’s been thrilling to watch.”

Throughout the process of translating Macbeth, Bracknell found herself grappling with notions of respect and reverence.

“How do you honour a Shakespeare text but also the ancient Noongar language?”

She feels confident she has created a work that celebrates both the Shakespearean language and tradition and Noongar culture. And importantly, Hecate not only showcases Noongar language but introduces people to the way that Noongar stories are told.

“We’ve created a theatrical experience that allows people to connect again – and that is what art should do. That is what the world really needs.”

Just like Shakespeare in his day was holding up a mirror to his society and challenging what he saw – Yirra Yaakin’s Hecate will do the same. At the end of the day it’s a play about grief and loss and humanity. So it’s something that all audiences can relate to – whatever language it’s in.